Originally included in the Winter 2013 issue of Aperture magazine, “Photography as you don’t know it”.

I didn’t exactly get lost on my way to the Archive of Modern Conflict—I had no idea where I was going in the first place. My appointment was for three in the afternoon, and at a quarter to the hour I was still on a bus to Kensington, searching my phone and diary in vain for an address which, oddly, I had neglected to request earlier. I can only think that an enigmatic reputation had started to work on my subconscious; it seemed like the sort of place one should fail to find: a collection seemingly devoted to one subject—the photographic history of war and violence— but whose holdings are in fact thematically unruly, merging with the history of the medium, with history in general. It made sense to think the archive had no fixed location. As it turned out, the Archive of Modern Conflict is more welcoming, more accessible, and still more mysterious than I’d imagined. After a swift e-mail from the top deck, I was directed to an address on a quiet residential street near Holland Park. Timothy Prus, curator and editor, would be waiting in the alleyway. For the past twenty-two years Prus has presided over a collection that, while it began as an archive of images bearing on the First and Second World Wars, has grown to encompass a frankly eccentric range of photographs—all of them apparently corralled into this West London warren according to the dictates of Prus’s curiosity, taste, and happenstance mode of acquisition. The archive hovers somewhere between the status of a museum with a strict historical remit and a private collection that ramifies according to visual and conceptual lines of inquiry as much as accident and whim. It was founded, and is still funded, by Canadian businessman David Thomson, owner of the Thomson Reuters media empire. He is notably shy of publicity, and Prus cheerfully deflects inquiries regarding Thomson’s reasons for setting up the archive, sketching instead the story of his own interest in vernacular photography. Prus was an art dealer until the archive took over his time, but had been buying old photographs since his childhood in the 1960s; working on the archive, he says, was a welcome corrective after too many years spent looking at abstract paintings. At present the collection includes over four million photographs, stored in London, Beijing, and Toronto. Prus is by no means tired of photographs of the wars of the last century, but his interests and expertise are considerably more vagrant and unpredictable. One way to gauge the oddity of the enterprise is to innocently ask Prus how he comes by all this stuff. He’ll demur regarding specific dealers and prices, but open up about the stranger sources and attendant stories. He’s most eloquent on the rhythms and the surprises essential to collecting: “If you enthuse about a crazy subject that you’re really interested in, and it’s genuine, then other people are enthused, and eventually, through some kind of mechanism, the stuff will arrive at your door. Sometimes you can wish for something, and it takes more than a decade to arrive. And it never turns up like you imagine it; it’s always a variant.”

The most visible outcome of this process of enthusiastic, intuitive, and patient collecting is a remarkably diverse program of publications and exhibitions, including fertile collaborations with artists. The books have included The Corinthians (2008), a hymn to the role of Kodachrome in documenting postwar American life; an unsettling survey of Nazis at leisure, entitled Nein, Onkel (No, Uncle, 2007); and the five small colorful albums that make up Silvermine (2013): a selection of snapshots salvaged by collector Thomas Sauvin from a recycling plant on the outskirts of Beijing. And the archive has so far published six installments of its own journal, each with a different format. The two most recent issues have accompanied AMC exhibitions: an enigmatically encyclopedic selection by Prus for Paris Photo 2012, titled Collected Shadows; and Notes Home, an exhibition of postcards from the east coast of England, curated last year by Prus and Ed Jones for the FORMAT International Photography Festival in Derby. As well as lending to exhibitions and museums, the archive welcomes scholars—though Prus is a little testy on the subject of researchers who turn up with a single historical hobbyhorse in mind: “They’ll hang around here for hours looking for, say, pictures of Middlesex Regiment belt buckles. And we haven’t got time for it.” He vastly prefers visitors who can bring something of their own imagination to the collection; on my way out later, I meet a young scholar who’s working on the mapping of the moon by Victorian engineer James Nasmyth. In the sort of conceptual and visual swerve that the archive makes possible, Prus is convinced that she will learn something too from underwater photography of the same era. I’ve arrived at the archive in one of the first warm weeks of the year: lunch is still on the table, and the doors are open to a yard where a handful of employees are busying back and forth from the basement with crates destined for Les Rencontres d’Arles 2013. I want to get some idea of what Prus is looking for when he acquires a set of images, and so he talks me through recent purchases, clearing a few plates and hefting a large hardback volume onto the table. It’s an album from the mid-1930s showing children suffering from strabismus, photographed before and after treatment with corrective lenses, with typewritten commentaries on each case. The text seems to imply, says Prus, who relishes the simultaneous absurdism and sadness of the book, that middle-class kids respond better to treatment than the economically disadvantaged. We pause when we realize that many of the children seem to have died during treatment—a squint apparently the least of their troubles. Obscure professional collections make up some of the most fascinating holdings of the archive: albums that are clearly either one-offs or were produced in-house by state institutions or private corporations in short print runs for limited circulation. Prus tells me he’s recently bought an album of First World War dentistry; then he gets out a volume, compiled during or directly after the same war, that depicts spies and traitors subsequently executed by the French state. The archive is catalogued by accession number; such is the variety of material in some of the discrete books, folders, or packages that thematic organization on the shelves would be impossible; keywords, accidents, and the expertise of the staff are the only ways to find what you’re looking for. Here is an album produced early in the twentieth century by the Glasgow shipbuilders Yarrow, showing in thirty-four hand-colored photographs a selection of craft manufactured for the Admiralty in the previous quarter-century. The boats themselves are precisely rendered, with crews lined up on deck, or have had their armored hulls peeled away to reveal weaponry inside. But what’s most striking is the exquisite attention to the calm blue-green of the sea and, in almost every case, a sky that turns to a delicate shade of pink as it nears the horizon. Next is a small envelope containing thirteen prints, again hand-colored, that reproduce the Magic Fountain of Montjuïc, designed by Carles Buigas for the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition. Relatively long exposure times have turned the water in the fountains, illuminated at night in candy pink and acid green and yellow, into bulbous lozenges of hazy but frozen water.

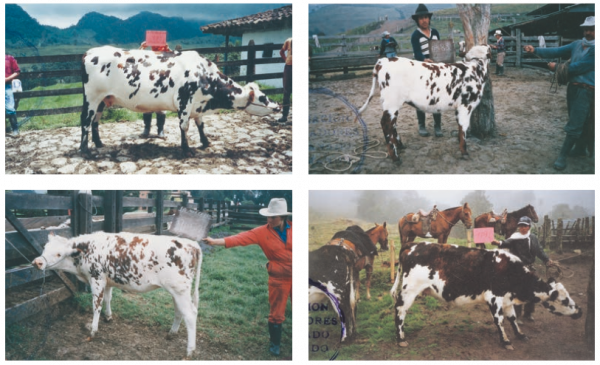

Another abiding interest, Prus says, is in “the alternative history of abstract photography. That’s taken me back to microscope slides and pattern designs and so on.” One of the more unlikely instances of this sort of abstraction is a collection, also just recently bought, from a flea market in Bogotá, of tiny prints in which Colombian cattle ranchers are photographed with their livestock. The farmers stand proudly with each cow, holding cards on which are handwritten names and numbers. The collection seems to have belonged to an association of Colombian breeders of Normandy cattle. Prus tells me that the seller claimed to have many more images in this line, but failed to turn up to a subsequent rendezvous. What really interests him is the visual typology that develops across the series, the way the animals’ markings deviate and repeat and seem to dominate the snapshots with their abstract patterns. If it’s sometimes hard to judge the degree of humor or whimsy in Prus’s engagement with some of the images in the archive, there is no doubting his assiduity in getting hold of them. At the time of my visit, he is overseeing the scanning of hundreds of color negatives from a commercial studio named Photo Jeunesse in Cameroon. Prus, having discovered the business being run at a loss by the son of its Nigerian founder, bought its archive of negatives from the 1970s and ’80s. He regales me with a tale of how he fell in a hole in the street on the same trip, and found himself lying in the hospital for many hours beside the fresh corpse of a road accident victim. The archive’s incomplete information on many subjects and its curator’s delight in the lurid tales that attend many of his researches and acquisitions perhaps hint at the attraction of this curious institution for contemporary artists. A long-term collaboration with London-based photographer Stephen Gill has resulted in several books. And at the time of my visit prints by Bruce Gilden lined a wall in the basement: starkly lit images of startled Londoners destined for a forthcoming exhibition and book. As regards artists’ relationships with the collection itself, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin have recently mined the archive for images of violence and catastrophe and used them to illustrate their edition of the King James Bible. There are car bombs and homicide victims, burning ships and atomic explosions—but also stage magicians and their paraphernalia, and more Nazis at play, laughing at a trained dog that’s jumping a row of chairs. If in contemporary art using found photographs has become something of a cliché, the Archive of Modern Conflict supplies artists with material that is at least heterogeneous and unpredictable, and as likely as not somewhat sinister. It is hard to determine from my time there, or from Prus’s description, where the exact impetus or the guiding logic for the archive now resides. It seems to function both as an authentic, well-funded resource for certain types of research into the minutiae of the conflicts of the last century and as an experiment in figuring out what photography, conceived in the broadest terms, might mean today. Comprehensiveness could in no way be the goal, nor a simple adherence to an idea of the vernacular photograph: the archive’s holdings intersect too frequently with the interests and the methods of contemporary artists for it to be considered a sort of image-dump for everyday or outsider material. Better, I think, to view the collection as an incomplete, maybe interminable, species of research in itself. I returned to the archive twice, and the second time spent some hours browsing the shelves. A fat green commemorative leather album contained photographs of all the principal players in the Dreyfus case. An Atlas of Gas Poisoning from the First World War reproduced drawings based on contemporary photographs. There were press-agency photographs of 1940s Parisian rat catchers, psychiatric patients in the Belgian town of Gheel in the 1930s, and celebrated transgender cases of the post-war decades. The scrapbook of a British Army bomb-disposal expert in Northern Ireland. More German soldiers: lounging in the sunlight in the Grand Place, Brussels, or freezing on the Eastern Front. A vast and gorgeous volume from 1903 outlining the “theory of textiles,” with jewel-like fabric samples tipped in. Pilgrims to Lourdes (in the same folder as the rat catchers). Plane crashes. Aerial views. Portraits Psychiatriques. Coming back out into the sunshine of a West London afternoon felt far too sudden—the world had not yet been completely anatomized, nor the results catalogued.

Brian Dillon is UK editor of Cabinet magazine and reader in critical writing at the Royal College of Art.