Socialist Flower Power: Soviet Hippie Culture is at The Wende Museum in Culver City, California, May 20–August 26, 2018

In collaboration with The Archive of Modern Conflict and Dr. Juliane Fürst of the University of Bristol, The Wende Museum is exhibiting the personal archives of several prominent Soviet hippies – including photos, clothing, and memorabilia.

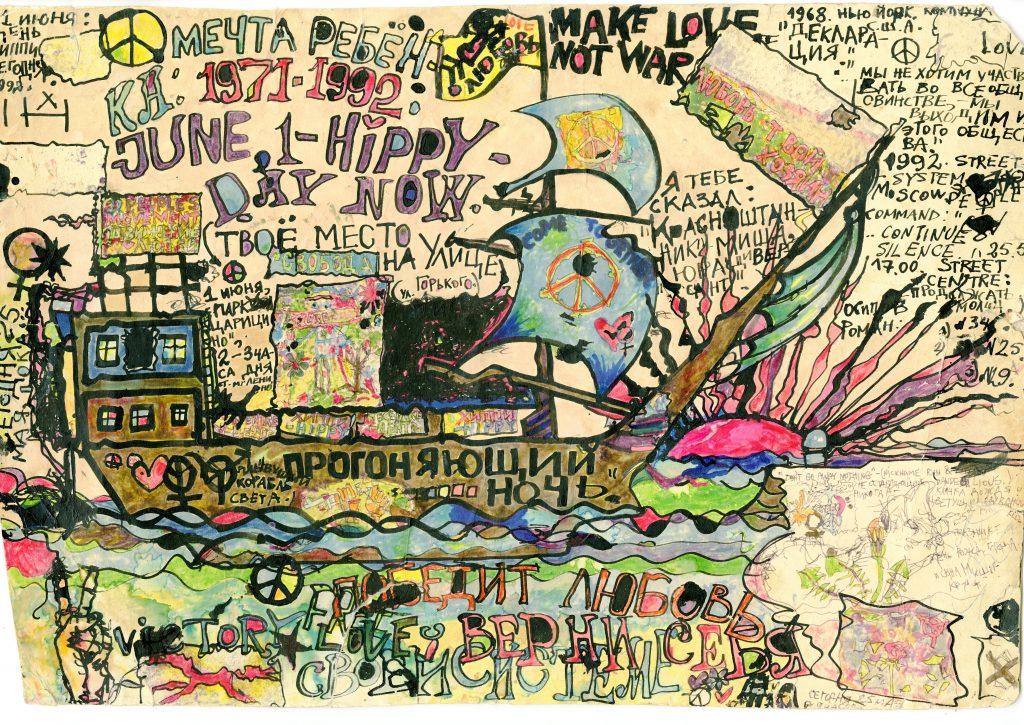

This exhibition is devoted to a world that few people know existed and that many find hard to believe did exist: the world of the Soviet hippie movement. Soviet hippies were part of the global counterculture of the 1960s and 70s: They wanted love and peace – and rock and roll. They maintained an elaborate network all across the Soviet Union. They experimented with homemade drugs. They studied Eastern mysticism and were looking for God. Yet they lived in a state which valued conformity above all else and mercilessly persecuted them for the way they looked and lived.

Hippies were the first truly global youth movement. Yet it is doubtful that the hippies of San Francisco understood how international their style and creed was. Indeed, when the San Francisco Diggers staged a funeral for the hippie movement in 1969, hippies across the world were just getting started. In Moscow, 1969 was a seminal summer for the band of hippies – translated into Russian as “khippi” – who had started to assemble at a few central places and in the apartments and country houses of their mostly privileged parents. It was in this year that Moscow hippies discovered that there were many of them, that they shared more than just long hair, and that the city was full of people who liked rock ‘n’ roll and jeans, and embraced love and peace as values more authentic and meaningful than Marxism-Leninism.

Hippies had indeed started to appear, independent of each other, in all major Soviet cities. Young people painted flowers on their cheeks in Riga, invented hippie symbols in Sevastopol, assembled on the main square of Magadan, in a cemetery in Lviv, opposite the Communist Party headquarters in Kaunas, and by the Finland Station in Leningrad. Their idols were the flower children of Haight-Ashbury, but their main source of information about them was the Soviet press. Soviet media initially paid a great deal of attention to the new anti-capitalist, collectivist-minded hippies of the West, covering them with sympathetic, wistful articles such as one in the journal Around the World called “Travels to Hippieland,” which was read by thousands of budding hippies back home, until the Soviet government started to see them as a threat.

This exhibition aims to give a glimpse into the world of Soviet hippies, a world that brimmed with intensity and excitement, yet also labored under the repression and constraints of the state in which it existed. In many ways this world will be instantly recognizable to the Western eye. There was love, sex, and rock ‘n’ roll. There were drugs, spirituality and the constant search for freedom and meaning. There were bell bottoms and beads, the burning desire to express one’s identity, to stand for something and to make the world a better place. Soviet hippies were undoubtedly one of the more remote and more unlikely outposts of the global 1960s counterculture. Yet their outward appearance obscures the fact that the most significant elements of their character were formed in response to what was close to home: the Soviet Union under Brezhnev and his successors.